We take a look at different kinds of building maintenance, with examples, to understand the importance of preventative or corrective measures

A home kept in good repair will be more energy efficient than if it has begun to develop structural and damp issues. Understanding broader maintenance types is another tool in your belt towards getting the best from where you live.

There are two types of maintenance work: reactive and proactive. Reactive maintenance happens when a minor issue has been left unattended for too long and has resulted in damage that now requires repair work. If the building is listed, it will complicate matters further as it requires a “like-for-like” repair.

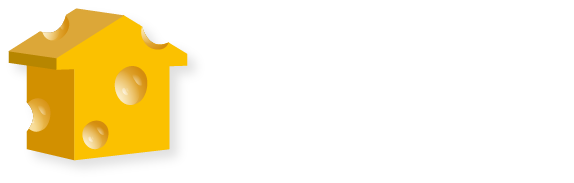

Look at this window frame for example, with the painting peeling off exposing the wood to moisture which has resulted in rot. Proactive maintenance, in this case, would have meant treating and painting the window frame before it has gotten to this stage.

Image credit: www.tywicentre.org.uk

Another example where regular maintenance work prevents greater damage, potentially structural damage to the building, is maintaining and repairing the render.

Image credit: www.tywicentre.org.uk

Water got behind the nearly impervious sand and cement render on this building. Moisture is trapped behind the render making the walls behind it soaking wet. This could cause internal damage to the building over time, if it remains untreated. Re-rendering the building would resolve the issue.

Examples of good and poor maintenance

On the pictures below you can see an example of a well-maintained building:

Examples of neglected buildings:

Rectification

A third type of building maintenance related work is when an intervention that was supposed to improve a building’s performance has done just the opposite: it needs to be rectified rather than repaired or maintained. An example for this could be a cement plinth installed at the bottom of a building that made the wall wetter not drier as its intended purpose was. A wet wall is a cold wall. Keeping buildings dry is critical to maintain a healthy and comfortable indoor environment. Here, water gets trapped within the cement plinth and is unable to escape. You can see cracks on the plinth: it is moisture trying to escape but it can’t get out. It makes the original wall behind it damper than it originally was.

Understanding Physics as it relates to buildings is critical for good retrofit design. Half of the battle is won by recognising bad design in these instances.

Image credit: www.tywicentre.org.uk

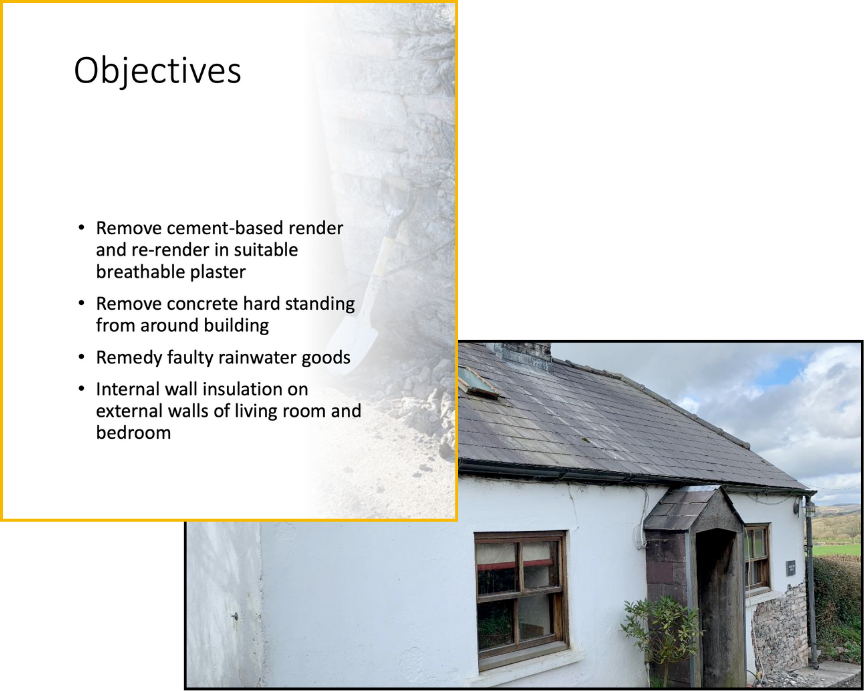

Another example for a similar “rectification” scenario is from a case study that was carried out by Joe Moriarty who is a consultant tutor and Built Heritage Monitoring and Enforcement officer at the Tywi Centre.

The case study is from a renovation project on a detached non-listed 18th Century lodge with cavity wall bathroom extension located in exposed rural location of the Brecon Beacons.

Concrete hard standing around the perimeter of the property, in conjunction with ineffective rainwater goods and poorly situated down pipe had caused moisture to become trapped behind failed render and had saturated the solid rubble stone walls constructed from mainly local limestone and earthen mortar to the point it had become visible internally.

The concrete hard standing around the building operates similarly to a pair of Wellington boots.

It keeps the water out until it doesn’t – water has its ways – and then it can’t escape. Water gets trapped similarly to the cement and lime render and the cement plinth, causing severe damp issues to the building. During the renovation project the concrete hard standing was removed and was replaced with a french drain.

Have you had any experience with issues that needed to be rectified rather than repaired to prevent further damage to the building?

Source:

Tywi Centre, Defects of Traditional Buildings (video)

Case study: Blaencwm Lodge, Llangadog, Carmarthenshire by Joe Moriarty

Written by Dori Jo